|

Artist Journal - Photo-Selene - © Lloyd Godman

Around 1969, I remember experimenting with off camera flash and torches in the landscape. I would photograph trees, grass etc. in the pitch black of night. The results were interesting but never resolved and the negatives were later lost.

At some point I always meant to get back to the technique.

|

|

On the way to the Murray Darling Palimpsest Conference at Mildura in 2006 we camped over night at Lake Hattah. The lake had recently been filled and along the lake shore were thousands of treed knee deep in water - each one had its own character and I began experimenting with off camera flash so as the illumination from the flash lit up the water in the foreground and the tree, but fell off behind the tree and left a black background.

|

|

As part of the trip we continued on to Lake Mungo where we camped around the far side of the Lunette. It was a moonlit night with a strong wind blowing white clouds across the sky. Here I experiment with laying the camera on the ground pointing up at the sky for 30 second exposures. The cloud became a ghost like blur with stars piercing bright holes through the fabric. The branches of the trees were also moving in the wind, which added to the effect.

|

|

During a workshop that I ran at Wilsons Prom in Feb 2007, I found a fantastic twisted tree trunk in the grounds of the Tidal River camping ground. But it was impossible to photograph without distracting extraneous details, so I began painting the tree trunk with torch light at night. I would place various coloured filters over the torch and paint the tree with light.

|

|

In october 2007, I ran a workshop at Lake Mungo. There was a full moon and we spent several hours every night photographing in the moonlight on the lunette. Working on the dunes was a magical feeling. The extreme heat of the day faded away, as did the hoards of blowflies - the night was a perfect time to work. The moonlight combined with light painting created some alluring images. I used the light from a high powered LED torch.

|

|

After the Burrinja show opened, I ran another workshop at Wilsons Prom, and engaged in a much more elaborate series of luna light paintings. Placing different coloured gels over the torch and selectively panting areas of rocks. However, the rock were far less reflective than Mungo and the exposures were much longer.

|

|

Gathering Falling Light

While at wilsons Prom I began experimenting with walking along the beach with the shutter open for 30 seconds. This was at dusk when the light levels were falling, and and it occurred to me that it was like gathering falling light.

Out doors, light falls like star dust from the heavens upon us where it is either absorbed or reflected. It manifests a recognizable likeness that we identify as ourselves or another. As photographers, we might take a photograph of these light modulations in a traditional manner to represent a person or object.

Light from the same source also falls indiscriminately around us, but like waves that crash on an isolated beach, stray light disappears without acknowledgement or trace. In this series of images I use the camera as a means of gathering up this falling light to slowly grow an image inside the camera. In a similar manner to the environmental artist, Richard Long, the images reference a meditative walk, in my case, along a beach in moon-light or a bush track at dusk. However, where Long uses a camera to document his walks, I actually use the camera as part of the process of walking. (I first introduced this concept into my work in 1993) For the duration of the exposure while walking, the camera is held at chest height, pointing forward with the shutter open for an extended period of time - there is no way to view the scene - only a sense of what might be projected through the lens. Many exposures of 30 second to several minutes are made during each walk, and in each the falling light is gathered through the lens of the camera. In the resulting images, a sense of time and vibration references the layers of light dust falling to earth.

All Prints – 432mm X 557mm Museo Portfolio Rag paper - 300gms with Epson Ultrachrome pigments

|

|

Early Observations and Experiments

The basic optical principles of the pinhole are commented on in Chinese texts from the fifth century BC. Chinese writers had discovered by experiments that light travels in straight lines. The philosopher Mo Ti (later Mo Tsu) was the first – to our knowledge – to record the formation of an inverted image with a pinhole or screen. Mo Ti was aware that objects reflect light in all directions, and that rays from the top of an object, when passing through a hole, will produce the lower part of an image (Hammond 1981:1). According to Hammond, there is no further reference to the camera obscura in Chinese texts until the ninth century AD, when Tuan Chheng Shih refers to an image in a pagoda. Shen Kua later corrected his explanation of the image. Yu Chao-Lung in the tenth century used model pagodas to make pinhole images on a screen. However, no geometric theory on image formation resulted from these experiments and observations (Hammond 1981:2).

In the western hemisphere Aristotle (fourth century BC) comments on pinhole image formation in his work Problems. In Book XV, 6, he asks: "Why is it that when the sun passes through quadri-laterals, as for instance in wickerwork, it does not produce a figure rectangular in shape but circular? [...]" In Book XV, 11, he asks further: "Why is it that an eclipse of the sun, if one looks at it through a sieve or through leaves, such as a plane-tree or other broadleaved tree, or if one joins the fingers of one hand over the fingers of the other, the rays are crescent-shaped where they reach the earth? Is it for the same reason as that when light shines through a rectangular peep-hole, it appears circular in the form of a cone? [...]" (Aristotle 1936:333,341). Aristotle found no satisfactory explanation to his observation; the problem remained unresolved until the 16th century (Hammond 1981:5).

The Arabian physicist and mathematician Ibn al-Haytham, also known as Alhazen, experimented with image formation in the tenth century AD. He arranged three candles in a row and put a screen with a small hole between the candles and the wall. He noted that images were formed only by means of small holes and that the candle to the right made an image to the left on the wall. From his observations he deduced the linearity of light. (Hammond 1981:5).

In the following centuries the pinhole technique was used by optical scientists in various experiments to study sunlight projected from a small aperture.

I was attracted to this image of Aristotle with this hand through the aperture of the window - titled the fall of Aristotle |

Aristotle's Fall -

tapestry, Augustiner Museum -

Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

The philosopher Mo Ti (later Mo Tsu) |

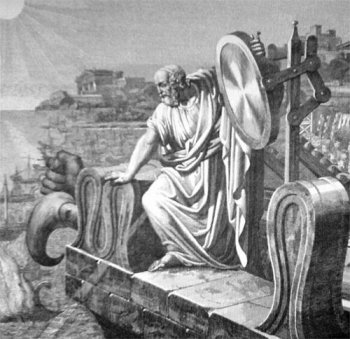

In this image Archimedes is with his burning mirror -

According to Plutarch, Archimedes reflected the Sun's rays onto the Roman galleys and set them alight. Such a story, true or not, was too good for the medieval chroniclers over a thousand years later to resist. Like the tabloid journalists of their day, they embellished the tale with details of their own until history and legend became hopelessly intertwined. Some of these later writers say that Archimedes used the polished round shields of the Greek troops to concentrate the sunlight, while others insist that he focused the rays with a giant single mirror. Joannes Zonaras, a Byzantine historian of the twelfth century, wrote:

At last, in an incredible manner, he burned up the whole Roman fleet. For by tilting a kind of mirror he ignited the air from the beam and kindled a great flame, the whole of which he directed at the ships at anchor in the path of the fire, until he consumed them all.

Archimedes 287?bc 212 first noted aspects of the pigmentation change in plant tissue due to exposure to sunlight and since then photosynthesis has been central to much speculative and scientific investigation. |

|

Uwe Bergmann explains his take on science with an old joke:

A guy comes home one night, really drunk, only to discover he’s lost his house key. He looks for it in the small circle of light surrounding a lamppost. A passerby asks him, “Do you really think you left your key there?” “I don’t know,” the drunk replies, “but it’s the only place with light.”

|