|

Drawing

from Nature explores representations

of nature and culture with the juxtaposition of a pencil & camera - © Lloyd Godman

Drawing

from NaturE

Lloyd Godman 1992

|

Text

Among

the ever-increasing array of mass manufactured photographic equipment,

few cameras if any produce images other than rectangular or square

in shape. From the smallest format cameras through the popular 35

mm to 120 medium format, 4x5 and even 8x10, from the assemblage of

the simplest to the electronic wizardry of the most complex, all are

based on an images shape with four sides.

We accept it without protest, as the archetypal form our images come

in.

Film

and paper are produced in

more efficient rectangles, dominance of the shape paper

neatly stored in rows, of rectangular paper ready This practice is not just whose roots in this area western tree

of ART: too-dimensional works

are is

the one unifying factor have in common before with a first mark or pressing to match this equipment further establishing the rectangle. Boxes of photographic contain individual sheets for use, 100 at a time. peculiar to photography, come from the great paper, canvas,

almost all centred

on this shape. It many western artists striking the blank material the camera

shutter. |

|

Our perception

of an ArtWork is almost almost certainly contained within the frame

of a rectangle and the exact space available within the 'frame'. The four

edges of the film are all-important in their work. The challenge

for them is the design of the image within the frame, and in many instances

this became justification for a lack of image content and meaning in the

work. The photograph

then, is rectangular only by our convention, although we sometimes fail

to be aware of the convention as such and take it as "reality" or

the given. The fact of image composition within the bounds of the frame

is enough and all the meaning needed.

|

If the analogy

with painting and the conventions of camera construction had not dictated

the rectangular shape of the photograph, the sheer efficiency of the geometry

might have done so anyway.

|

The Rectangle is without doubt

the primary building block of our structures, however small or

large. Whole cities are built on the concept of four sides, from

the broad aerial view of street patterns laid out below to the

macro view of a small book within one of the buildings, or further

inward to the circuit of a computer. It is a modular shape which

when laid end on end , side by side or one on top of the other

continues to clone itself as a reinforcement of the paradigm.

|

Property

developers, and their associated promiscuous assemblage of money-lenders,

accountants, etc. welcomed the modernist movement with open arms and fatter

bank accounts as an opportunity to finally remove those ornate but expensive

intricacies of form and embellishment from the construction of new buildings.

When space and finance are at a premium why produce an intricate

facade when the very structure itself could act as one, urbane and smooth?

To cut all this unnecessary decoration and expense; and all under the

guise of ART!

Is

it little wonder then that the modern movement , besides being supported

by western political ideologies, was embraced whole-heartedly

by the property developers and industrialists of the time as a discreet

way of advocating the removal of expensive decoration from architecture

under the pretension of the avant-garde. Because of our perception of

time. always moving forward we may be willing to accept without question

or thought that any change in society and its manifestations advance

forward also. Perhaps now, left behind is the legacy of this experiment,

gigantic structures piercing the spiritual line of sky and earth and

mirror glass reflecting nothing more than itself. A reflection of us,

our culture and unquestioned change. The achievements of our age that

are in flux with the continuation of change to this metaphysical line.

Naturally

textured blocks of stone hewn from raw irregular deposits

within the earth, fall neatly into place as rectangular curb stones

of a large but 'ordered city. Our weight is upon them, without

recognition of the stones' origin as we cross from one side of

the street to the next. Large impressive slabs of polished marble

veneer on a building street frontage are rarely thought of by

the constantly moving shapes reflected on its surface. Modern

building foundations driven deep into the earth as rods of cemented

steel, then extended from these structural supports in a familiar

unimaginative shape, the rectus bulk reaches high, skyward despite

the plasticity of concrete and the infinite possibilities

of form, visual surprise and sensory stimuli it offers. So much

of our design, with the

exception of a few rounded corners, conforms to this rectangular

standard. Photographic negatives; small rectangular images

of silver or dye embedded gelatin, produce photographs of similar

shape and are often stored in rectangular album. Or, perhaps,

neatly framed in rectangular frames, mounted on cleanly cut rectangular mat board, the rectangular photograph rests as an icon to its

own shape. It sits on a clean white rectangular wall within a

rectangular structure and administered by a person, possibly of

rectangular thought, at rectangular desk, with a rectangular catalogue

of the same exhibition. It is all very neat and delicately wonderful!

We can see it at any gallery of any city; it is what we

are conditioned to expect. In harmony with this machined rectangularity

is the sympathetic sophistication of the glossy photographic surface

which reflects the technological

achievements of its time. It exudes a sense of regularity and

a smooth clean synthetic surface. Instrumental in the birth of

photography was the need to quickly and more realistically produce

n image of the real world. Painting and graphic arts had attempted

this task but most often only exposed their shortcomings. Somehow there

was always the interpretation of the artist, the characteristic marks

of the medium involved or some other idiosyncrasy that removed

the reality of the subject (of course it was later debated by

some, suffered from all of these as well).

Photography

on the other hand produced the most remarkable likeness imaginable,

accurate in detail, texture nd perspective. It squarely threatened

the pseudo realistic merrymakers of the time in a way no one could have

predicted with its unmatched strength later turned against it and criticized

as its achilles heel by the critics nd cynics.

1)

Charles Blanc made the point 'Photography copies everything and explains

nothing, it is blind to the realm of the spirit'.

However,

photography ws fathered by the endeavors of traditional mark-makers

and a need to draw. When the simplistic but exquisite marks in

the caves at Lasux were made, could the makers ever have perceived

the conceptual idea of a camera and associated chemical process

needed to produce the photograph? Their mark-making at

the time was innovative enough.

|

Evolution

of thought and perception crates a material need within the human

species. The cerebral perception of flight stimulates the desire,

which leads to the experimentation, invention and finally the

reality. The physical evolution needed for human flight is immense

while the intellectual evolution to allow us flight is minor by

comparison. This is one feature that holds us apart from other

life forms on the planet.

|

We

can't fly but our invention can!

Do not science and art need this

process of invention for their very

survival and growth? the excitement

of the creative-inventive act can

defy explanation while motivating

extraordinary amounts of human

energy in the quest for the

illusionary answer (just ask my

wife Elaine and and my friends).

It can be one of the most

frustrating, enigmatic but

revealing and fulfilling human

encounters. |

|

At

the time of invention, the

photograph pointed to the future.

At last the sacred code of image-

making had been broken and

photography transformed the

perception of art forever. Great

debates raged about its validity

as art, even to the point of court

cases. The act of machines

creating images was also

questioned, some seeing it

as an ultimate act of

blasphemy and a sure step to

Armageddon, even doubting the |

possibilities

of its existence. However, photography had broken the consecrated

code of image-making and in the eyes of some should be tortured

and tormented for this sacrilege forever. These bigots survive

even today, usually clinging onto the crumbling structure of easel

painting in a world of mass images transmitted through fiber optics

radio waves and digitization. They defy traditional values of

painting as king in a desperate bid to sustain a hierarchical

structure. Despite conservative, elitist and precious attitudes,

photography has become an effectual and rewarding way of making

creative images. It has become another tool in the expanding visual

vocabulary and is at present argued by some as at the cutting

edge of contemporary visual art being one of the primary mediums

of exploration. It has helped expand the boundaries of art without

doubt, even of painting itself.

It

invokes a sense of magic to see an image materialize on a blank

sheet. Perhaps it echoes an ancient ancestral memory of alchemy

and sacred codes broken in dark and mysterious places centuries

before in the quest of earlier secrets. Is not photography the

act of turning silver into a visual 'gold'?

|

|

|

Once

the precious

code had been

found, a flood of

refinements and hybrids

like 3D stereo, video, holograms

etc. were sure to follow. At last the hand seemed

free from the evolution of physical mark making and the

problem of communication between the mind command and the

physical act. Realistic images of unequaled quality could be

made at will

and in a split second with a mechanical device and a chemical

process. As democratic

as it sounded an educated photographer or discerning viewer

can always see the difference between good and bad photography

(in technical terms at least). A virtuoso in any medium emanates

a lasting presence to those in tune; though in flux due to the

contemporary elements since its creation, the purity of sound

continually resonates a quality beyond time. The idea that photography

is an easy art may have some truth, but only in the context

that it is also easy to

|

|

paint

a mark on a canvas and as in painting where not every mark on

any canvas is of some worth, so with photography not every photograph

is of value. In fact few are. Great photographs are hard won.

Conceivably, in terms of two-dimensional art there have only

been two major technical developments, the mark produced by

the hand and an image projected by a lens. Photography also

pointed to an age of machines,

industrialization and a synthetic environment alien to the old

world.

There could be no turning back. The world was changing

again, and as the photograph became a symbol

for all the innovation that nurtured

its existence. The camera

and the photograph

are the origin

of all

|

other descendants

including TV etc. that have

become

symbols of our time. Each

is a symbol of our tech-

nology, a symbol of our

command of materials, a symbol

of our ideas and a symbol

of so much, even without an image on

its surface. An icon to

our inventiveness, our cleverness. But the photo-

graphic family also stood

as a symbol for further reaffirmation of the rectan-

gle. And yet there was an

immediate contradiction to the rectangle. All lenses are

circular and project images

of a similar shape from which we then cut this neat clean

rectangle. The terms circle

of confusion and circle of illumination both relate

directly to photography. and yet from this circle we determine

to cut another shape. Centuries before

photography, artists used

the camera obscura to draw images from and were and were unaware

of this circular image projected through the lens. From the

simplest pinhole "lens" to the most expensive lumps of ground

glass, the projected image is circular. Human vision is also

a contra-

diction to the rectangle,

being more elliptical, while our perception is undeniably not

rectangular.

In photographic terms the

world is an infinite expanse in front of the lens, a circular

one through it and a rectangular one behind it. Despite its

efficiency, the rectangle is the most peculiar of shapes in

the context of the natural world.

The natural world is

an endless erratic mass. Although it is of apparently simple

comprehensible

order, it is unparalleled

in its perplexity of overlapping, interlocking and ever

changing array of

shapes that are

unconforming to geometric rectangles.

While there are gardeners grooming

organic rectangles,

the spontaneous flow of shape, form, texture, colour,

light and shade of

nature produce a super

intricate variegation unmatched by any or all of our structures.

The

human appreciation of

this complexity requires a subtle perception few people are

prepar-

ed to cultivate. A perception

astute and complex enough to take in much more than the

patterns of the

picturesque. An awareness which transcends the

obvious while

leaving no doubt

that any extended perception only increases that

chasm be-

tween the known and the

unknown.

I

Lie on a hill, this mound of earth

I feel the sky vaulted above me

Below I sense growth and flux

The stillness vibrates a relaxed

silence

I

am nowhere and everywhere at once

Recharging, absorbing, purifying

My heart is is synchronized with a larger pulse

The vortex of an earth stone in space

An unfolding universe, a grain of sand

The intoxication of infinite spin

How am I above this organic growth

yet below its understanding?

I NEED TO RETURN AGAIN.

The

notion that the source of the value 'beauty' may reside in an

undisturbed landscape, like the rectangle, is of our convention.

Without the ability of perception, the landscape just simply

exists while the implication by our standards may be that it

somehow contains beauty. The concept of beauty is of our invention

and is open to personal interpretation which may be constantly

in flux due to a multitude of experiences and reason. The general

interpretation of beauty in landscape during the 19th century

in New Zealand was greatly different from the general beliefs

of today; even though complex variations of that interpretations

exist today.

A Maori perspective may differ greatly from that of the Pakeha,

while the ideas of a primitive "civilization" with no

contact with the outside world we may not even be able to guess

at. And yet why do we continue to physically abuse the environment?

2) Our discouragement

in the presence of beauty results, surely, from the way we

have damages the country, from what appears to be our inability

now to stop, and from the fact that few of us can any longer

hope to own a piece of undisturbed land. Which is to say that

what bothers us about beauty is that it is no longer characteristic.

Unspoiled places sadden us because they are in an important

sense, no longer true.

Few places are isolated

and unchanged enough to remain in the spirit of wilderness,

and if we can find them there is always a fascination with

them that may lead to their change.

And is the movement away

from these these conventional landscape values as being unfashionable a reaction to its assumed association with other accepted

values of society? In doing so we may risk the very essence

of our survival on this planet while attempting to support

ideologies that are reactive to societies conditioning. It

is convenient to have an apathetic society who regard the

environment as not beautiful or such a cliché

as hardly worth mention, when the motive is to exploit the

environment in an unsympathetic and destructive manner. Unfortunately

do not most reactive anti-society movements in the end fall

victim to the fate they are trying to avoid, exploitation?

So often the message of an ARTWORK is lost by the monetary

value, the the very fate it might have been trying to avoid.

The

purchase of a work about the protection of the environment by

a large corporation becomes ironic when that very corporation

decides how much of the environment it will exploit in the board

room where the work hangs. I know they need to hear the message

louder and more often than most but is not the message for them

the inflated price tag, the brand name. It is an icon to investment

and their own wealth, not a protection of environment.

Should this not be the very reason to Love these untouched places before they are gone, but

not Loved to a point of extinction as we so often do?

I may feel the intense desire to escape the conformity of our

constructed civilization by placing my body and spirit in the

peace and isolation of a wilderness area. My photographic works

relating to this experience may clearly reveal something of

the undisturbed nature of this environment and act as a warning

of the delicate balance persuading a sense of caring, love and

emotional possession for the place in the viewer. Where an image

or a likeness of a place will not satisfy and only the place

will do, that passion may also create such a longing of the

viewer's personal presence in the place that it could ultimately

lead to the destruction of the object of both our fascination:

the undisturbed environment.

Do

I have the liberty to enter these precious areas in preference

to others? Is the nature and the experience of what I do as an

artist enough to permit entry in preference to another of more

modest background? For if they are never permitted entry their

mana and perception my never grow. But if I do enter, is it not

the attitude and sensitivity that may allow entry without undue

disturbance? Is there not some responsibility to find and experience

(perhaps in a photograph) the uniqueness for theses remaining

places and bring them to the attention of at least one other individual

before they are gone? A shadow, footprint and a photograph are

the softest evidence I can hope for in my journey through these

places. Breath softly on the land and feel its heart beat.

Do

I have the liberty to enter these precious areas in preference

to others? Is the nature and the experience of what I do as an

artist enough to permit entry in preference to another of more

modest background? For if they are never permitted entry their

mana and perception my never grow. But if I do enter, is it not

the attitude and sensitivity that may allow entry without undue

disturbance? Is there not some responsibility to find and experience

(perhaps in a photograph) the uniqueness for theses remaining

places and bring them to the attention of at least one other individual

before they are gone? A shadow, footprint and a photograph are

the softest evidence I can hope for in my journey through these

places. Breath softly on the land and feel its heart beat.

If

we did decide to abandon the present momentum of technological

invention (progress) and opt for complete return to nature,

does this mean return to the the darkness of caves and

food before fire? I feel few of us could tolerate the relinquishment

of creature comforts needed to allow even a small modificion

n our life styles besides the trauma of a total upheaval. But

if we ignore the organic nature of ourselves, our dependency

on the organic planet and the fineness of the balance, like

many other life forms, we may not be part of the ecosystem in

the further. We may be destroying the most valuable structure

of shelter and creature comforts we have in an effort to improve

our well-being, after all this planet provides us with shelter

from the storms of space and the rain of the universe while

providing enough comforts for our continued survival. We have

to ask the question, do we need the planet to survive or does

it need us? Do we continue forward but only with our priorities

drawn more seriously from organic nature?

The

instinctive idea of beauty in the landscape may be naive but

it may have some protetional value if enough people revere it.

Political change can occur if we act in unison however deep

or shallow our philosophical base is and whatever our beliefs

and values. A more sophisticated perception however may take

a lifetime commitment to evolve to a point of meaning or any

understanding by strength of human spirit nd focus unmoved

by the fleeting fashions and trends.

3)

"In the beginning those who knew the Tao did not try to enlighten

others, but kept them in the dark.

Why is it so hard to rule?

Because people are so clever

Rulers who try to use cleverness

Cheat the country.

Those who rule without cleverness

Are a blessing to the land.

These are the two alternatives.

Understanding these is Primal virtue.

Primal virtue is deep and fr. It leads

all things back

Towards the great oneness."

As

the saying goes' we are what we eat', is it also true "we my

become what we wish to become' if we wish it hard enough? Through

perseverance one may accumulate vast amounts of money, while

n openness to the land allows a oneness with the earth. Could

each perceive the other from their relative position?

In

a wilderness area each intricacy seems dependent upon the other,

suggesting natural visual ecosystem; the dislocation of

one piece reacts with the others that remain. To perceive this

system is to experience the unity-in-complexity of organic form.

A natural cohesion with a conditioned alternative o its own

logic and direction, a sensitive chaos. There are geometric

patterns in nature, but each struggles for its own durability

creating a visual irregular sophistication unobtainable with

the "indispensable" structure of rectangular form. To relate

with the human eye this visual harmonic may require much more

than just a sense of sight.

While

the building materials of modern city are concrete, glass and

steel, the structure of wilderness tracts are from the ancestral

elemental symbols earth, air, water nd fire. Their manifestation

being in the form of moist rich soils, remains of the generations

before; great swirling clouds, driven from the very breath of

the planet; free flowing rivers and streams musical in their

search for an end; and great rocks and ash, reminders of volcanoes

and lightning strikes, a fusion of this unity-in-complexity

of organic form presents a visual challenge created over the

mellennia into the areas we cll wilderness. A prolonged period

of several days or more in this environment presents the possibility

of becoming sensitized mentally to the visual irregularities

and unfamiliar rhythm of patterns of the surroundings. This

unaccustomed sensory stimuli may result in an overload

of the cerebral conditioning, demanding a rectangle or at the

very least simple straight line. However given more time

and an open sensitivity to the 'here and now' we can reach a

point where, confronted suddenly with a small rectangular sign

post or similar object, amongst the inter-weave of variegation,

we feel jarring of the organic rhythm and the sign

may emerge as alien as a cosmic-string.

This sensation, can and is most often

experienced by the 'average person' while driving through vast

areas of open county for hours or even days and at last coming

to few modest signs of civilization. Sometimes they my

feel the sensation, but are paralyzed to find meaning

or explanation, letting it expire without comment or cerebral

acknowledgment. If as an individual we cause an action on our

environment and can see no immediate harmful reaction, we are

only too willing to accept the reaction as insignificant or

imaginary when in fact it my be super slow slow motion

suicide. This ultimate action is imaginary and of doubt until

consciously acknowledged, by which time it may be too late to

react effectively.

4) Althusser describes he human subject

as being in n imaginary relationship to it existence.

The

nuclear debate is the classic example, 'if you can't see it,

it is probably harmless'. Perhaps it is this detached relationship

between the physical and the cerebral that yields to a logical

conclusion in the fallout of the nuclear issue? There are so

many examples where we actioned chemical change to the environment

and we allow this to accumulate without any real concern

for the future. The ultimate pessimist may argue that the supreme

conclusion of us as a species is extinction and through the

rapid exploitation of the environment the sooner we destroy

ourselves the better for the planet.

The purchase of a work about

the protection of the environment by a large corporation becomes ironic

when that very corporation decides how much of the environment it will

exploit in the board room where the work hangs. I know they need to hear

the message louder and more often than most but is not the message for

them the inflated price tag, the brand name. It is an icon to investment

and their own wealth, not a protection of environment.

Should this not be the very reason

to Love these untouched places before they are gone, but not Loved to

a point of extinction as we so often do? I may feel the intense desire

to escape the conformity of our constructed civilization by placing my

body and spirit in the peace and isolation of a wilderness area. My photographic

works relating to this experience may clearly reveal something of the undisturbed

nature of this environment and act as a warning of the delicate balance

persuading a sense of caring, love and emotional possession for the place

in the viewer. Where an image or a likeness of a place will not satisfy

and only the place will do, that passion may also create such a longing

of the viewer's personal presence in the place that it could ultimately

lead to the destruction of the object of both our fascination: the undisturbed

environment.

Do

I have

the liberty

to enter these

precious areas

in preference to

others? Is the nature

and the experience of

what I do as an artist enough

to permit entry in preference

to another of more modest background?

For if they are never permitted

entry their mana

and perception my never grow. But

if I do enter,

is it not the attitude and sensitivity

that may allow

entry without undue disturbance?

Is there not some

responsibility to find and experience

(perhaps in a

photograph) the uniqueness for

theses remaining

places and bring them to the attention

of at least

one other individual before they

are gone? A

shadow, footprint and a photograph

are

the softest evidence I can hope

for in my journey through these

places. Breath softly on

the land and

feel its

heart

beat.

|

| If we did

decide to abandon the present momentum of technological invention (progress)

and opt for complete return to nature, does this mean return

to the the darkness of caves and food before fire? I feel few of us could

tolerate the relinquishment of creature comforts needed to allow even a

small modification n our life styles besides the trauma of a total upheaval.

But if we ignore the organic nature of ourselves, our dependency on the

organic planet and the fineness of the balance, like many other life forms,

we may not be part of the ecosystem in the further. We may be destroying

the most valuable structure of shelter and creature comforts we have in

an effort to improve our well-being, after all this planet provides us

with shelter from the storms of space and the rain of the universe while

providing enough comforts for our continued survival. We have to ask the

question, do we need the planet to survive or does it need us? Do we continue

forward but only with our priorities drawn more seriously from organic

nature?

The instinctive idea of beauty in

the landscape may be naive but it may have some protetional value if enough

people revere it. Political change can occur if we act in unison however

deep or shallow our philosophical base is and whatever our beliefs and

values. A more sophisticated perception however may take a lifetime commitment

to evolve to a point of meaning or any understanding by strength

of human spirit nd focus unmoved by the fleeting fashions and trends.

3) "In the beginning those who knew

the Tao did not try to enlighten others,

but kept them in the dark.

Why is it so hard to rule?

Because people are so clever

Rulers who try to use cleverness

Cheat the country.

Those who rule without cleverness

Are a blessing to the land.

These are the two alternatives.

Understanding these is Primal virtue.

Primal virtue is deep and fr. It

leads all things back

Towards the great oneness."

As the saying goes' we are what

we eat', is it also true "we my become what we wish to become' if we wish

it hard enough? Through perseverance one may accumulate vast amounts of

money, while n openness to the land allows a oneness with the earth. Could

each perceive the other from their relative position?

In a wilderness area each intricacy

seems dependent upon

the other, suggesting natural

visual ecosystem; the dislocation of one piece

reacts with the others that remain.

To perceive this system is to experience the unity-in-complexity of organic

form. A natural cohesion with a

conditioned alternative o its own

logic and direction, a sensitive chaos.

There are geometric patterns in

nature, but each struggles for its own

durability creating a visual irregular

sophistication unobtainable with the

"indispensable" structure of rectangular

form. To relate with the

human eye this visual

harmonic may

require much more

than just a

sense of

sight.

|

| While the

building materials of modern city are concrete, glass and steel, the structure

of wilderness tracts are from the ancestral elemental symbols earth, air,

water nd fire. Their manifestation being in the form of moist rich soils,

remains of the generations before; great swirling clouds, driven from the

very breath of the planet; free flowing rivers and streams musical in their

search for an end; and great rocks and ash, reminders of volcanoes and

lightning strikes, a fusion of this unity-in-complexity of organic form

presents a visual challenge created over the mellennia into the areas we

cll wilderness. A prolonged period of several days or more in this environment

presents the possibility of becoming sensitized mentally to the visual

irregularities and unfamiliar rhythm of patterns of the surroundings. This

unaccustomed sensory stimuli may result in an overload of the cerebral

conditioning, demanding a rectangle or at the very least simple straight

line. However given more time and an open sensitivity to the 'here and

now' we can reach a point where, confronted suddenly with a small rectangular

sign post or similar object, amongst the inter-weave of variegation, we

feel jarring of the organic rhythm and the sign may emerge

as alien as a cosmic-string.

This sensation, can and is most

often experienced by the 'average person' while driving through vast areas

of open county for hours or even days and at last coming to few modest

signs of civilization. Sometimes they my feel the sensation, but are paralyzed

to find meaning or explanation, letting it expire without comment

or cerebral acknowledgment. If as an individual we cause an action on our

environment and can see no immediate harmful reaction, we are only too

willing to accept the reaction as insignificant or imaginary when in fact

it my be super slow slow motion suicide. This ultimate action is

imaginary and of doubt until consciously acknowledged, by which time it

may be too late to react effectively.

4) Althusser describes he human

subject as being in n imaginary relationship to it existence.

The nuclear debate is the classic

example, 'if you can't see it, it is probably harmless'.

Perhaps it is this detached relationship

between the physical and the cerebral that

yields to a logical conclusion

in the fallout of the nuclear issue? There are so many

examples where we actioned chemical

change to the environment and we allow

this to accumulate without

any real concern for the future. The ultimate

pessimist may argue that the supreme

conclusion of us as a species is extinction

and through the rapid exploitation

of the environment the sooner we destroy

ourselves the better for the planet.

How ironic when he creative inventive

act has a destructive climax as

with the nuclear

issue.

In contrast, one small tree isolated

pathetically in a jumble of concrete would hardly raise an eyebrow. Is

the difference a conditioning of sensitivities? Have we no been conditioned

since we left the womb to encounters of the rectangular kind? Our first

spatial encounter outside the warm inner-sphere of our growth chamber was

with four encompassing walls we call a room and does not this conditioning

continue rarely interrupted throughout our lives? For many the wilderness

is also a space of obscure proportions, a space of trepidation, a foreign

environment. A place where the thorns of the undergrowth bite and claw

at the flesh the surface is uneven and rough to the feet and the fears

of one's own mind hide behind the girth of every tree, a place not to be

entered alone.

Do we always live secure inside

and on occasion venture outside? Or do we live outside and sometimes shelter

inside? Perhaps we do live a perceive different lives? The abstract

perception of one conflicts with the other. Is this a reason that so-called

"environmentalists" and "developers" are at loggerheads?

One may have the subtle perception of the planet at heart, while the other

perceives all areas as needing to be "rectangularity" developed though

always to their financial profit and at the expense of the "living". Is

New Zealand still a "landscape with too few lovers " , a place with a "sense

of order belonging to the land but not yet it's people"?

This conditioning may also occur

in our understanding and perception of our food source. Food surely comes

in packets, cans, and wrappers and sits on supermarket shelves awaiting

our selection is passed across the counters of fast food outlet or is presented

in an aesthetic manner at the hand of a well dressed attendant at an exquisite

restaurant. Food has nothing to do with the organic structure of the planet

and the right mix of pure water and sunlight, meaning we can mix these

up a little in a civilized world.

Harsh synthetic environments with

no reference to organic structures become

dead with no place for the impromptu

patterns of nature. However,

despite the striving to divorce

ourselves from

the organic domain, references

are ever

present.

|

D

RIP!

DRIP!D

RIP! DRIP!

DRIP!DRIP!

DRIP!DRIP!

DRIP!DRI

P!DRIP

DRIP

Fallen rain still gathers drop by

drop... slowly accumulating until the

broken meniscus causes it tit dribble

off the the oily-residued road surface

in long streaks running with acceleration

toward the sidewalk gutters.

The it flows in ever increasing

streams in a gush of disappearance down the grilles of a catchment drain

and out of sigh.

Feathers and leaves lost from their

primary purpose swirl as gossamer and in a wild wind dance find their way

into the synthetic corners to frustrate cleaners.

Forgotten seeds with defiant germination

and benign strength thrust upward through the covering of pavement seal

in an effort to reach the sun and a chance at life.

In the minutest cracks of the shiniest

mirror- tower blocks the moss spores activate and grow along with small

ferns towards an organic reorder in an environment designed o rebuff it.

The thin husk-like carcasses of

dead insects lie discarded, decomposing by the actions of the elements,

while their descendants survive by searching and enlarging the cracks in

crumbling concrete.

While .........

amongst the glass and glitter, mesmerized

stands the civilized beast gazing upward.

Tranced by a golden glass-refected

haze, pulse of lights and the rush of feet; the last contemplation is of

the fabric of the earth and the continuation of organic growth.

And yet, as mentioned, this stubborn

organic structure survives quiet in growth, unseen in places of ignorance

and neglect.

Aware of the rectilinear harshness

our structures create, we sometimes make a deliberate attempt to soften

them with plants etc. At best with great success the plants grow, exceeding

our estimation; their vigor offers an interesting juxtaposition and

different geometry to our adaptations.

More often, ready-made lawn is out, shocked juvenile plants bedded in,

a good thick layer of wood chips dumped on and

the edges given a strong 'tickle

up' with spray to kill any weeds with enough

audacity to surface. Presto! Instant

organics and a public visual display of

a sensitivity o the the environment.

Then, left to its own devices in a plot

scraped sterile of its topsoil,

the plants struggle to survive on the

remaining clay, while rocks

lie like fish out of water, inanimate

to the elements, dead.

Fox Talbot collated his early photographs

in an album titled "Pencil of Nature"

around 1834. His interest in photography

came from his fascination with

the natural qualities of light

and the frustration of his inadequacy to

draw a likeness. His invention

solved the problem and he likened

the camera to a pencil.

(5) "The idea occurred to me: how

charming it

would be if it were possible to

cause these natural images

to imprint themselves durably and

remain fixed upon the paper!

And why should i not be possible?

I asked myself .... Light, where it exists,

can effect an action, and in certain

circumstances does excert one sufficient

to cause changes in material bodies.

Suppose then, such an action could be

executed on the paper; and suppose

the paper could be visibly changed

by it. In that case surely some

effect must result having

a general resemblance to

the cause which

produced

it'.

|

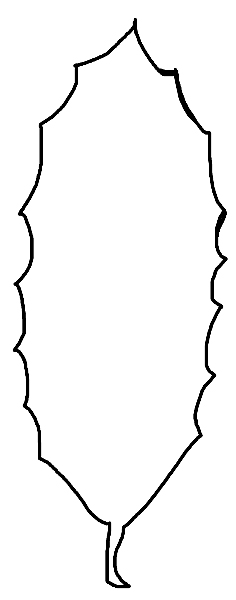

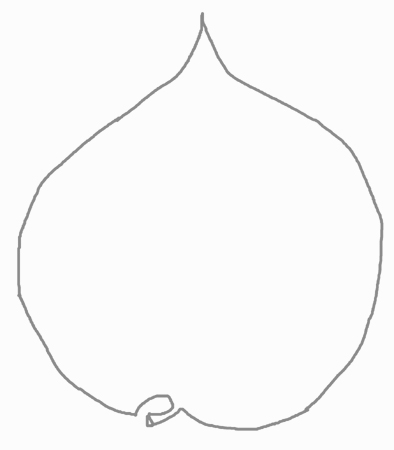

Does the combination of pen line

and photograph question a variety of orders? Could there be a deliberate

juxtaposition of the surviving natural components in the transposed environment?

Does pre human Auckland persist in the centre of humanized technological

Auckland? Is one organic and irregular; the other synthetic and rectangular?

As of this time can we return to the cave, or are the synthetic and the

organic inextricably linked and within or beyond our control? Have we little

control over the ultimate recipe of technological and organic fusion, a

recipe that began with or inventiveness, our cleverness and may end in

our destruction? In an effort to move forward, just exactly how much more

should we sympathetically draw from the complexities of nature? This expanded

drawing from the natural segment of the photograph may offer a suggestion

towards the concept of acknowledgment of our organic composition. It may

suggest the need to become more sensitive to the synapse of technological

progress and the essential constitution of life on this planet.

Do these images disjoin the rectangular

rectangular with the inclusion of an organic fragment outside the rectangular

form; but still within the ultimate boundaries of a rectangular frame?

The use of the drawing to break the frame and emphasizing the nature of

the organic form through he irregular shapes on the page may act as other

symbolic suggestions. The implied juxtaposition of the time differential

between the drawing and the photograph may relate respectively to the organic

elements

and synthetic structures. Whereas the photograph can be exposed instantly

recording the scene in front of the lens and then processed within a short

period of time, the drawing is built up slowly by a myriad of inter-lacing

lines laid down one at a time until the illusion of tone, depth and content

are created like a multiplying of cells. Metaphorically, the time scale

of the evolving organic nature of the planet defies age while the ability

of human kind to manipulate the environment is as that of the camera shutter

that exposed the film; about one sixtieth of a second. As a symbol, the

camera may also refer to the action of technology and machines as an accelerant

on the destruction of the organic order of the planet.

Is the mixing of media a reference

to the relevance, ideology and sophistication of each as an allegory? The

photograph has always been associated with the 'real', it is a document

of the circumstance hat existed in front of the camera at a specific place

and time. In the early years it was referred to as a 'system of nature

imitation'. The power of the photograph is that we believe it, there is

a conditioned truth implied we are willing to accept. A drawing, by contrast,

may not have existed at all. One may be imagined, the other real; but which

one? Conceivably it is the drawing that assumes a reality in terms of an

important message. These photographs are monochromatic and act as an abstraction

of tone, time and dimension on the image not present in the primary experience;

hardly real. The photograph symbolizes the 'developed environment' through

its own process while the line somehow unrefined and erratic may refer

to the 'undeveloped' by implication of he former. But it is the photograph

by its nature that is crucial to the inter-face of the two allowing us

to be convinced by the collision. Do they elicit a response about our perceptions

and attitudes we have to the environment and our rectangular reactions?

A photographic characteristic is

reproducibility. The ability to print and reprint from one original, in

a similar manner to the way we produce our synthetic products and technological

constructions. A drawing assumed as an original insinuates this exact unreproducibility,

it is a single item. Like the planet it is unique; it can not be mechanically

manufactured or repeatedly molded. Conceivably the drawing in these works

may also actuate as a device suggesting the uniqueness of the planet and

the complexities of such a replication.

Perhaps

there are also

metaphoric symbols about

ourselves and the way we treat

each the? An image of roots wishing

to

break free from the confines of

an allotted plot of turf.

The free form of upraised branches

firmly, whimsical, organic brace.

These may relate to the way we

act upon each other in the experiment of life.

Undoubtedly there is a complexity

of meaning for each viewer to discover;

an uncoding of symbols in a future

yet to pass, a reference of the past, of the present moment and the post

modern.

But will we listen, and more important,

if we hear, will we act?

Is not this organic, synthetic

debate about being human on an

organic sphere adrift in the

vastness of space.

|

|